“To transform the world there is no need for a new social system. What is essential is a group of men and women with social ideals. But such persons can survive only in a society [a culture] where there is purity of mind and good character. For those two qualities to flourish the basis is spirituality.”

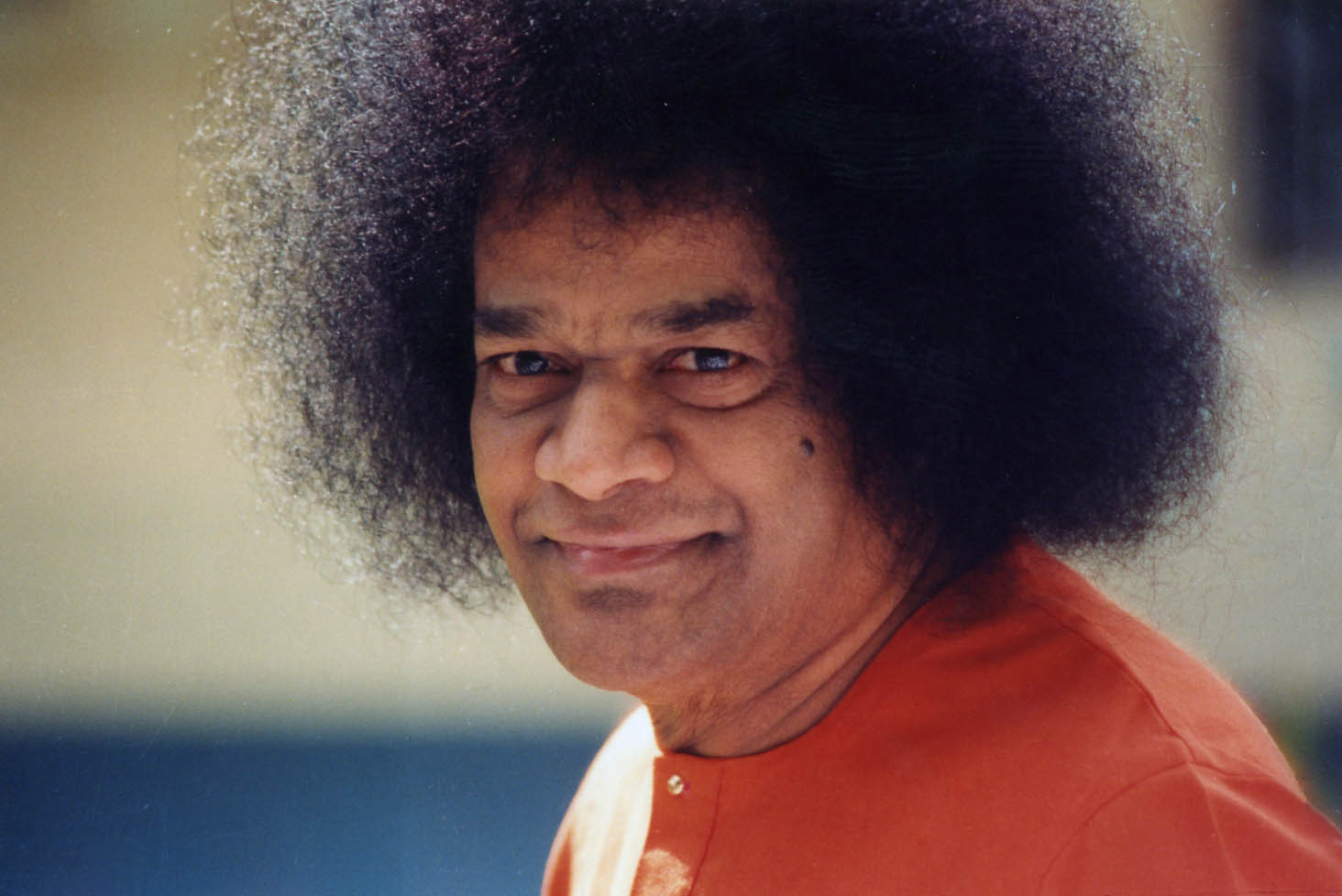

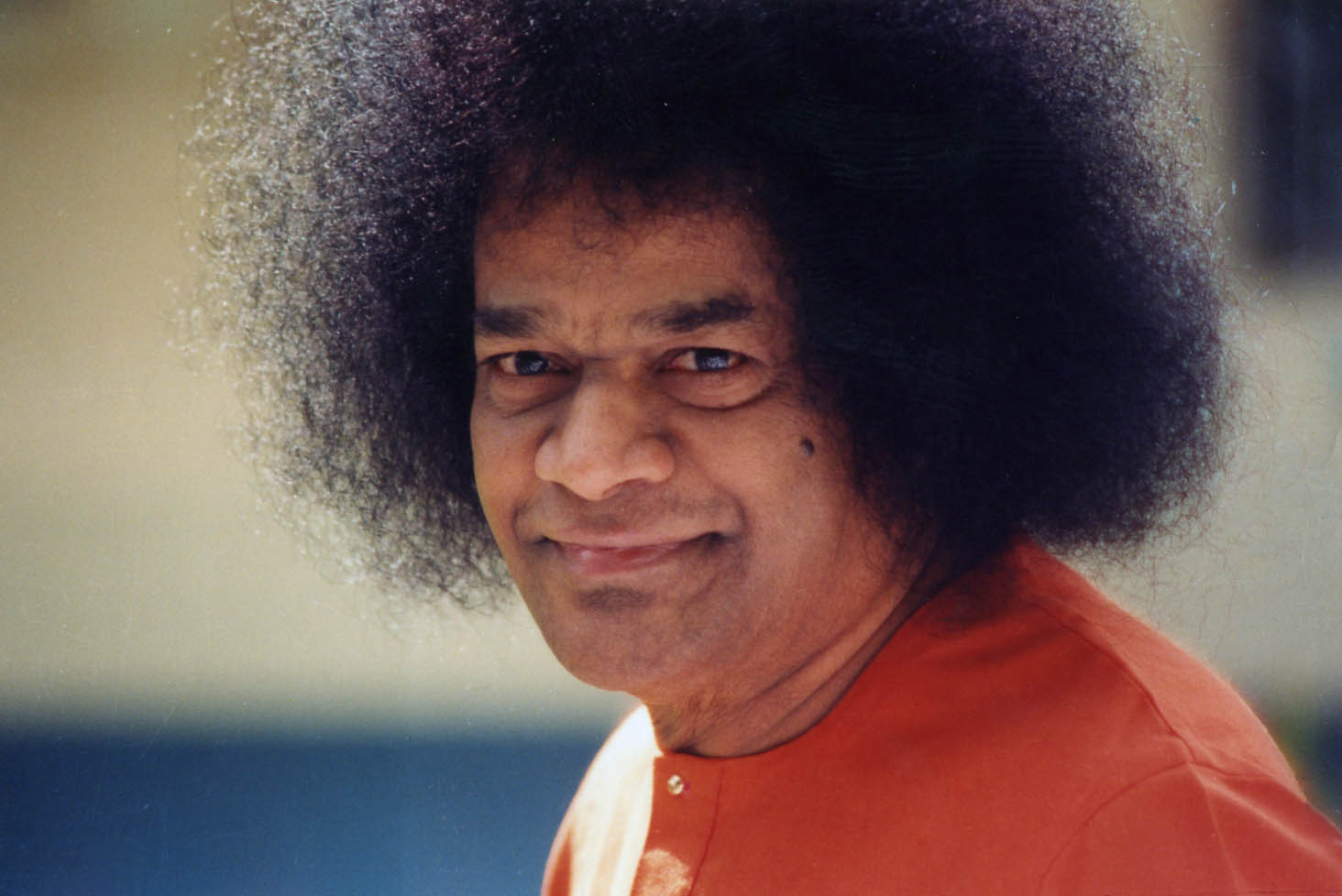

— Sathya Sai Baba

It’s a long way, spiritually and morally, from the Avatar’s mountain top in Southern India to an executive board room in Southern California. Or perhaps it is not so far.

The motor trip to Kodaikanal lifts us from the stifling, searing heat of the plains first through rolling foothills. The world outside the car windows gradually transforms from dusty, dry browns to green. Then the road narrows and becomes a winding mountain road climbing steeply through dense forests. Arriving finally at the top, hours later, we first notice the fresh cool air washing this little resort community.

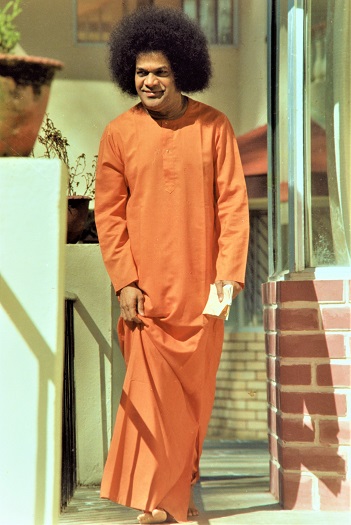

At daybreak in the quiet, almost chilly morning air, Baba’s devotees from all over the world stream out from their guest houses in all parts of this small town, towards Baba’s residence for Darshan. Even the mist rising from the cool mountain lake seems to move silently toward the driveway of Bhagavan’s bungalow, as though joining the people to catch a glimpse of the Avatar.

A few years ago Baba asked me to talk to the students at His bungalow in Kodaikanal. “Oh-oh, I’m in trouble,” I said to myself as I entered the neat parlor of Swami’s bungalow and made my way through the group of students to His chair. He motioned me to take Padanamaskar and softly said,”Talk about Dharmic Management.”

I stood to one side, looked at the students, uttered a quick “0m Sai Ram” under my breath, and began. “Bhagavan directed me to write a book on Dharmic Management,” I said. “At first, I thought writing it would be a simple task because I have over thirty years experience as a management consultant in ‘organization transformation’—which is the infusion of new energy, heart, and spirit into human organizations. But when I dove into the vast idea of Dharma I found myself occupied not only with the knotty problems of people in modern organizations but in the most profound spiritual questions and moral dilemmas facing people down through the ages.

This is beyond my capacity, I thought, but Baba, as though reading my mind, called me to Him and reassured me, ‘You have everything you need to write this book. I will help you.’ And later He told me, ‘Don’t worry whether your writing fits with My teachings. Write from the heart; your inner voice is Me.’ Even with those calming words I found myself constantly turning inward to call on Baba for help.”

“Not only was I trying to deal with some of the most profound queries of mankind (basic questions of values, purpose, spirit, and happiness),” I continued, “but I knew that most prospective readers would not be Sai devotees or even spiritual people. To grab and hold their interest the book had to respond to their problems and concerns. So I began to look closely at the eight or nine issues of most concern to management people (profitability, marketing, finance, motivation, and so forth) intending to answer those questions from a human values and spiritual perspective.”

“Over the following months, as I delved into these diverse questions, the answers began to sound strangely alike. My local mind rebelled, ‘How can answers to such dissimilar questions be so similar?’ I returned to the issues and dived even further into each, as though spiraling deeper and deeper, eventually into the very centre of them. When I reached this core level I found that the answers were not merely similar, they were exactly the same. Each of these issues required precisely the same remedy. At this profound level there is but one answer for all these questions!”

The boys were leaning forward not to miss this curious answer, ‘And that one solution can be summarized in one word,” I said. They leaned closer, ‘And that one word is … Love.”

“Yesss!” Baba immediately chimed in, startling everybody. All the boys’ heads snapped at once toward their beloved Bhagavan. Baba then spoke three words, nodding slightly to lend emphasis to each word. “Love ... is ... God:’ He said, and sat back.

As so often happens with our Bhagavan, all the pieces suddenly fell into place and made perfect sense. We’ve heard Him say it many times, but in that setting it came to life and became real. Suddenly –the Great Truth is our Truth too: when we finally arrive at the very deepest (or highest) level of any issue the answer is always Love.

This essential spiritual Truth sounds perfectly local in that sacred environment there on the mountain top in the presence of the Avatar of this age. But what happens when one comes down from the cool freshness of that place to the heat of the so-called real world of business? It seems a long, long way from up there to down here in most organizations that I work with.

After returning to the USA, I found myself in the board room of a new client company talking to the top management team about “personality patterns” that develop in organizations. It was an interesting company, founded by a goodhearted Hollywood movie star to create jobs for needy people from the ghettos and barrios of Los Angeles. But the company was in a hard-fought, competitive, industry, and had found itself in business trouble. Reacting to the trouble, the company was beginning to tighten up and thus lose its kindness, which was its soul. I was standing at the front of the room reaching to make a point.

I drew a horizontal line on the chalkboard, planning to use it to show a range of behaviors toward employees. “To help us understand an organization’s basic ‘personality,’ let’s use a reverence continuum,” I said. I was a little surprised when the word reverence popped out of me and noticed several brows wrinkling and some quizzical looks. “Oh-oh, I’m in trouble,” I said to myself again, and breathed an ‘0m Sai Ram.’

But I had seen those kinds of brows before and, believing that my little prayer would work, I trusted that this session would turn out okay. So I moved ahead, explaining that an organization’s characteristic pattern of behavior could be plotted somewhere along this chalk line, depending on the quality of human relationships within the organization.

Then I drew two short vertical strokes about a third of the way along the line. “This represents the dividing plane between basically ‘uncivilized’ and basically ‘civilized’ organizations. To the left of this plane are the mean spirited, indifferent, and apathetic organizations. Unfortunately, there are too many of them nowadays. Disregard those bad companies for now” I X’d that segment. “Let’s only consider companies to the right of the plane, organizations that are basically civil.”

I then divided this civilized portion of the line into four segments. “There are gradations of civility,” I said, pointing to the first segment. “The most elementary ‘civilized’ organization personality is the Polite organization.” I labeled the segment P.

“People in these Polite companies,” I continued, “are at least minimally considerate of and attentive toward one another. These are organizations with ‘manners;’ there’s a whiff of common courtesy in the air of them.” I searched my mind for an example. “The English as a nation are generally good at this. Even if they don’t like you, they will at least act politely toward you most of the time. It may be rather thinly veiled, but they seldom let themselves dip below a basic minimum level of civility.”

“But these Polite organizations better be careful,” I said half-jokingly, “because if they persist in this politeness it will grow, and they will slip over the line into real Caring. I scratched a C in the next segment of the continuum.

“The Caring organization is the Polite organization, but even more so. In the Caring organization members are more attentive, more thoughtful and more interested in people — and they’re more concerned about the company and the quality of their product. In this organization you see them watching out for one another and for customers.”

I gave an example, an incident in a particular high-production pharmacy unit in a huge medical center. “The unit operates as a human prescription-filling machine,” I said. “You walk into that workplace and all heads are down, churning out thousands upon thousands of medical “scrips” under great pressure each day. There’s a whole squad of professional pharmacists behind a long glass partition busily filling prescriptions, and there’s a score of clerks working the front end of this huge human apparatus, pecking at computer terminals and dealing with the throngs of patients that constantly stream up to the many windows at a very long counter. One day an old man shuffled slowly up to one of the windows and asked in a weak, shaky voice for diabetes medicine. Every head in the unit, whether pharmacist or clerk, looked up to make sure the patient wasn’t ‘in trouble.”

With this example the wrinkled brows in the group smoothed out some as these ideas were beginning to make sense. I continued, feeling a bit lighter, “But even Caring organizations better watch out because those behaviors, too, become a habit. If they aren’t careful, their caring expands into respect.” I labeled the third segment R.

“Respect! Imagine an organization culture (or a society) saturated in respect. Respect is one of those qualities we all know when we feel it, and are especially aware of when it’s missing. And yet, basic human respect is not thought about or talked about much in the business environment.”

I then asked, “What are the important human interactions and feelings that make up a respectful organization?” ‘The group helped build a list: being considerate toward one another, holding others in esteem, admiration, kindness, and so forth. It was a good list. “That’s the kind of organization I hear people all over yearning for,” I said. Their body language told me they agreed.

Turning to the chalkboard I put a big R in the final segment of the continuum. Remembering the strange word reverence they realized where I was headed and shifted uncomfortably in their seats. I pushed on anyway, “And respectful organizations should really be careful because when an organization constantly practices respect it becomes a habit—and that habit eventually deepens into Reverence.”

- Dr. Jack Hawley

Management Consultant and Former Visiting Faculty

Sri Sathya Sai Institute of Higher Learning